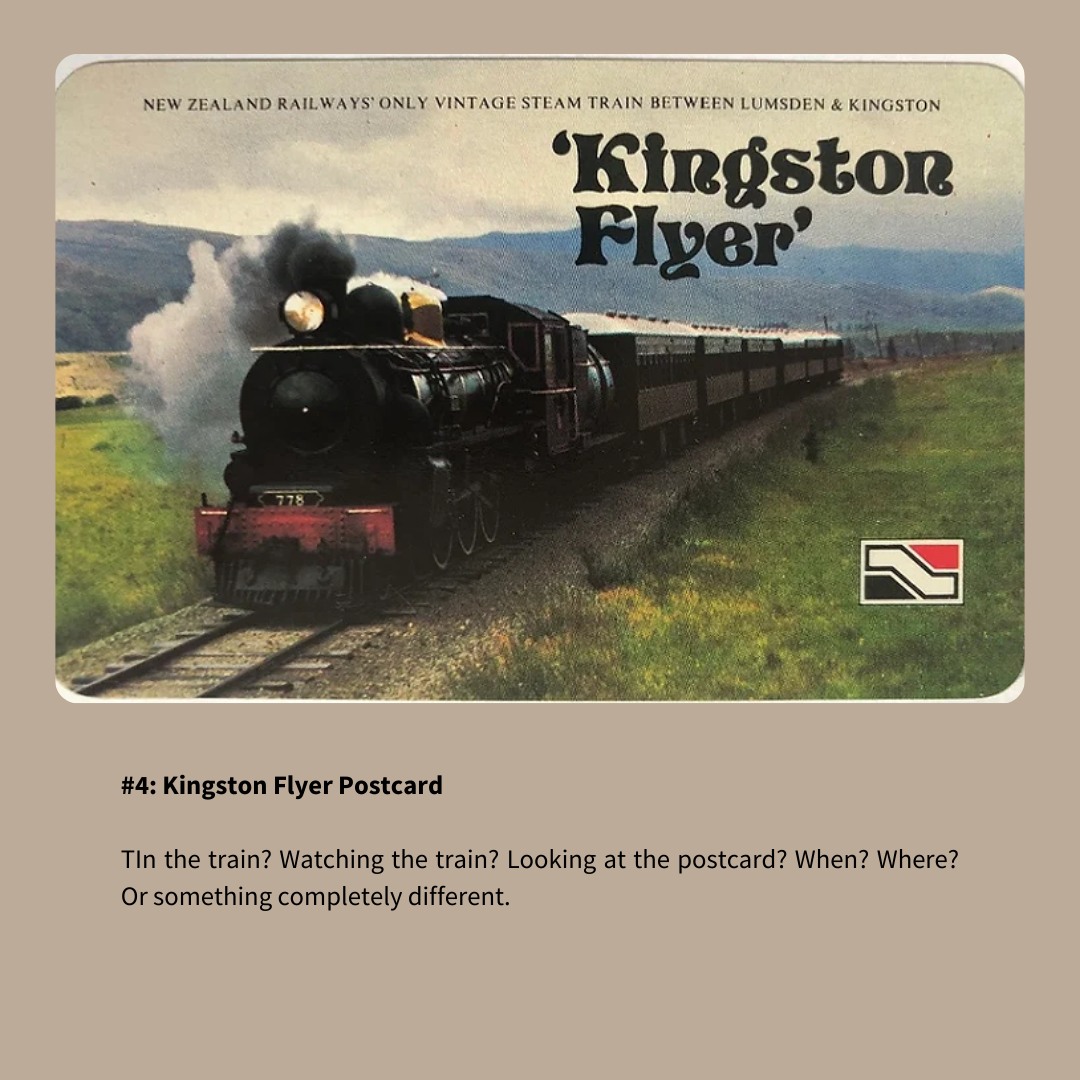

I recently entered a competition and won with this short piece inspired by the image of the Kingston Flyer on a postcard.

https://qtwritersfestival.nz/competitions/

Thanks so much to Anna-Marie Chin Architects for the generous prize and to Pip Adam and to the Queenstown Writers Festival.

Look out for this piece in the upcoming summer edition of 1964 mountain culture journal!

Geochemical Postcard

Coal is shovelled into the furnace, heating the water until the steam it produces generates enough pressure to push the pistons in the engine up and down. The pistons push the cranking rods to move the flywheel and the driving rod makes the wheels turn.

The coal is dusty and ancient. The shovel is made of steel. Steel and coal are kin. Born of and for fire. The sky above is filled with the breath of the earth, black particulate and piercing steam. The locomotive inhales heat and exhales power, its breath matching time to the scrape of the shovel into the coal bunker, the shattering sound of coal hitting coal, scrape, shatter, chugga, chugga, scrape, shatter. It becomes a dance for the stoker. He hears the hammering of horses inside the blast pipe

Someone three carriages down raises a tall glass of iced water to their face. The meniscus sways left to right left to right as it is tilted toward the lips. A brass curtain rod catches sun and the iced water glows amber.

Rocks of coal rest against each other in the belly of the firebox, no longer dusty and black they glow deep red and orange and white. Tiny suns radiating heat and light they haven’t felt for millions of years. They shrink as they burn. Gone, rising into the sky.

From a wooden-plank bench at the station a child stares down empty railway lines, fixated upon the vanishing point. Finally a puffy cotton mass appears to crest the closest hilltop, and the curved valley expels a steaming, smoking steel dragon. Fueled by fire and earth. Steam obscures the station; the child is in heaven.

A woman pulls large brown lenses over her eyes and looks into the falling glow, waving. Her hair, her skin, her handbag drenched in the warmest moments of afternoon sunshine. Her luggage has been placed on the platform, pointing her toward the pick-up spot.

A spark fires into a cloud of gas, igniting it and in the ensuing expansion drives a piston up a cylinder. Compressed air shunts through a valve and the camshaft turns and the crankshaft turns and and the wheels turn and the vehicle leaves the ancient breath of fauna behind.

Concrete and asphalt can only take so much; after decades the cracks and dips beg to be environments. A crown daisy pushes green into the edge of the gutter, where water seeps from a cracked PVC downpipe and over the tilted pavement. A town car passes and the shoot shudders in its tailwind. Above the shoot a green and brown stain spreads like the slowest steeping of tea. Tannins have settled into microscopic pockets upon the aged surface, bound to the crystalline structures, to serve as lowlights for the bright algal blooms of spring.

With blackened duck canvas coveralls removed to the waist, a filthy man sits before a stoneware plate at a slim rimu dining table. After grinding rough rock salt to fine sand over his fried eggs, he smiles as ancient minerals continue to serve him; he licks a white crystal from his index fingertip and thinks of the coal shovel. He is tattooed by the coal dust, the primitive grime of the industrial powerhouse sits stubbornly in every cuticle crease, each eyebrow follicle, the large pores at the sides of his nostrils. Black. As the fork raises to the mouth, two hepatic knuckles, calluses smoked like hocks, gleam in contrast. Where his moustache is not grey, it is yellowed. His sclera too. He is at home in clouds of smoke.

The woman from the pick-up spot is leading a dog toward a park. They contribute to the soundscape with the jingling of the leash’s brass hardware, stiff claws clacking on the footpath, soft scuffs of rubberised soles. One steps upon a twig. The other gets a leaf caught in their hair.

The stoker keeps fire in his eyes. And with every scrape and shatter, he smiles. The brutality of earth, the power sitting idly within. Energy released by the sun and held within plants and buried by time. Those eggs will be broken down by the enzymes and catalysts comprising his system. Energy released from the sun, to the grass, to the chicken, to its egg, to a stoker’s latissimus dorsi, to the shovel, to the furnace.

The dog chases a ball on a wide lawn as a solitary high-pressure sodium street light blinks on. The dog and the woman hear the whistle of a steam train leaving the station five miles over. It barks. She whistles for the dog to come; it’s time to go home.

Copyright © 2024 Jasmine O M Taylor

Jasmine O M Taylor [she/her] is a tangata Tiriti, pākehā, bisexual poet with a fixation upon mukbang and the sky. She lives in Ōtepoti with her true love and two black cats.